Not Seeing Ghosts

by Sarah Williams

Now that I am in my mid-sixties I find I have a long list of anti-achievements to my name, and, topping that list, the feat of spending two long summers in a haunted house and failing to see a ghost. This isn’t any run-of-the-mill haunted house either because Heol Fanog, high in the Bannau Brycheiniog, is now being described in the media as, ‘the most haunted house in Wales’. To be fair, I think the apparitions may have arrived long after my childhood holidays there.

If you walk uphill from Heol Fanog, you quickly leave the domestic world of hedgerows, hill farms and gated fields behind you. Stepping across a threshold, marked in my memory as a rattling metal cattle grid and a rowan tree, you find yourself in an unearthly landscape. There are steeper folds ahead of you before you reach the cold, round glacial Llyn Cwm Llwch under the high peaks of Pen y Fan and Corn Du — the lake that casts its spell on the valley.

I’m not going to re-tell the haunted history of the Heol Fanog, partly because it has been covered so many times in recent years. The Danny Robins podcast The Witch Farm, for the BBC, and Mark Chadbourn’s book Testimony, are good starting points for anyone who doesn’t know the story. I think I first heard about events at Heol Fanog shortly after the local paper, The Brecon & Radnor Express, covered the haunting in the early 1990s. Could otherworldly manifestations be drawing power from the national grid? Did this explain the impossibly high electricity bills landed on the Rich family who had moved there in 1989?

There is another reason I don’t want to dwell on the supernatural tonight. I am writing this on my own in a Welsh cottage. It isn’t Heol Fanog, but I am not too far away, on a slightly more far-flung orbit of the mountain peaks. And there’s a storm coming. Pen y Fan is hidden, but the great dark chimney of Corn Du appears now and then, topped by a deep mauve swell that glitters unnervingly, like the cloud formation over a volcano. As soon as I start to write, a salvo of cracks and bangs emanate, Heol-Fanog-style, from the fabric of the cottage itself. I quickly find the source of this: the gale stripping beech mast from a churchyard tree and hurling it at the cottage windows. Then comes a sudden brisk run of footsteps overhead — this in a cottage empty except for me. The long, white building contains two cottages, I remind myself, and they are plugged together in slightly strange ways: these footsteps are, I hope, the neighbour’s excitable dog.

A few days later, my brother I sit down together to talk about Heol Fanog. There are things about it that I can’t put in place without him. When exactly were we there and why? Who was the woman who rented the house to us? Did we see anything there we couldn’t explain? Anything scary?

In the end, I dated our first visit by one of only two things that summer that really frightened me: it was in one of bedrooms of Heol Fanog that my mother told me the Rivers Authority planned to flood our family valley by damming the Afon Wysg (River Usk). My imagination must have been influenced by the underwater world of the 1960s TV series Stingray because, under the new reservoir, I imagined a terrible re-shaping: the once-familiar stone bridges, farms, churches and barns becoming slowly encrusted by sinister, neon-coloured coral. Mum told me that when the heavy machinery rolled in, she planned to lie down in front of it.

There’s little online about the Big Usk reservoir project (though I did find some relevant Hansard), and the plan was relatively quickly shelved, but the threat remained hanging over a nearby valley, the Senni, for longer.

It is this threat that places that summer as 1968; I was eleven, my brother eight.

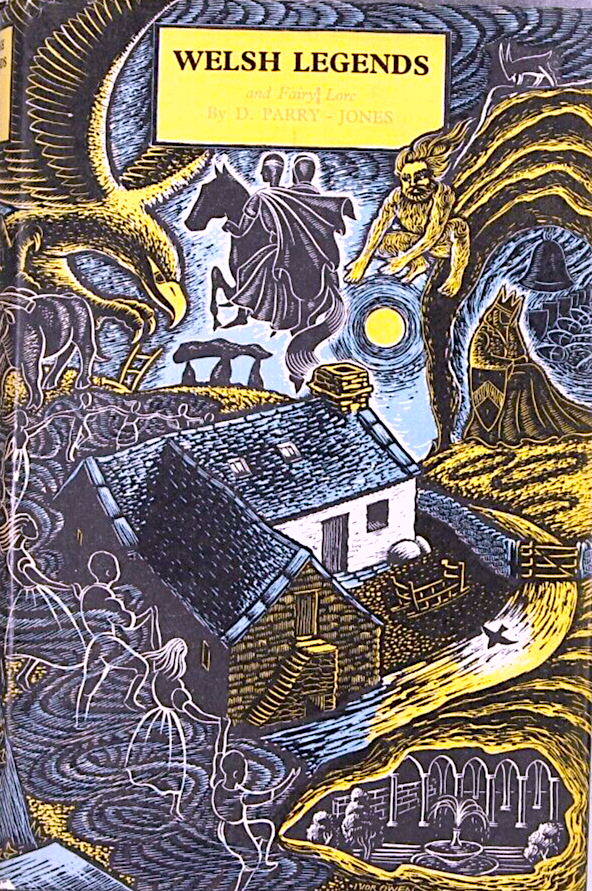

The eleven year old who stayed there would have been very disappointed to find herself in a haunted house and not see a ghost. I loved Welsh legends and folktales: Ysbrydion, spirits, Gwrachod, witches, the Tylwyth Teg, fairies and the Cannwyll Corff, or Corpse Candle: a kind of ‘fetch light’ said to flicker along the remote ‘coffin paths’ that were used to transport the dead from more isolated communities to a burial ground. Cannwyll Mair – Mary’s candle – is a rare but more appealing variant. Local stories too: Llyn Cwm Llwch, under the high peaks above Heol Fanog, is a silvery threshold to the land of the Tylwyth Teg — one that only opens once a year.

I’ve said there were two things that frightened me that summer, and I’ll come back to the second in a moment.

llustrated by Ivor Owen

It was just part of our summer routine: we’d stay with my grandmother near Aberhonddu (Brecon) for a spell and then head west to wild Welsh beaches anywhere between Marloes and Aberaeron. This year, dad seemed to want to stay closer to home. My brother and I remembered his original plan clearly: renting a more remote and basic cottage high in Cwm Llwch. I think this idea was quickly vetoed by my mother: a place without electricity or running water; two small children; her own nervous mother; a spaniel who liked to chase sheep? Dad rented the next house down the mountainside instead — which was Heol Fanog.

Heol Fanog was an enchanted place. To the excitement of those of us in the back seat of the car that summer, the road we took to it was sometimes closed and a ‘Danger’ sign put up, indicating that the army were on the mountain that day, that he firing range was live… this, oddly, contributing to the feeling of being in a secret, protected world.

It was Marion Holbourn who showed us around before we moved in, I am quite sure of that. She is mentioned in the media as having moved out in the early 1960s, perhaps to a retirement home, but she was certainly still there in 1968. It was her son who rented the property to the Riches in the 1980s, by which time the ghosts had arrived.

Mrs Holbourn struck me as a determined, energetic and robust woman, kind to children, full of ideas for creative projects… slightly bohemian perhaps, though I am not sure I knew that word then. She was renting out her house, I believe, because she was going to Scotland for the summer.

Mrs Holbourn told us to expect occasional visitors because she was creating a garden for the blind at Heol Fanog. I am afraid my brother and I, nervous for their fate, practiced for such an arrival by blindfolding each other in turn and going round the garden seeing how many holes we fell down or obstructions we tripped over. There were a great many hazards, including the ruined foundations of the original house mentioned in accounts of the hauntings. I don’t remember these dangerous ruins very well; my brother says he was intrigued by them rather than frightened: intrigued, perhaps, because he was forbidden to play there.

There was something that frightened my brother though, and he describes this as a Saracen helmet complete with a length of chain mail that hung — inexplicably, as far as he was concerned — in a downstairs room at Heol Fanog. Well, I wasn’t scared of it, because I happened to know from Mrs Holbourn that it was simply a prop for a pageant. I don’t think I was sisterly enough to reassure my brother: I kept this knowledge to myself.

~~~~~~~

Were we nervous of the house itself? Not of the building, which was originally a barn and a relatively new conversion of the 1950s. I remember stone, wood and quite a light airy feel to it, and nowadays we might say it had a Scandinavian style interior but I am not sure that was yet a concept in 1960s Britain.

I remember a passageway that ran alongside four or five rooms upstairs where a set of black and white pictures were displayed. I was fascinated by pen and ink drawings as a kid, such as Tove Jansson’s illustrations in the Moomin books. I really liked the lively drawing at the end of Heol Fanog’s passage — fierce sea and clashing rocks; a landscape empty of people; cleverly drawn so that everything seemed to be in motion. Its mysterious title was ‘Ultima Thule’.

The other illustrations did feature people but I was too nervous to look more closely. There was a large pen and ink drawing in one of the bedrooms, you see, that terrified me; my grandmother firmly turned it to the wall. I was frightened of snakes — a phobia that has never left me — and this image showed a lovely woman wrapped in a large python. Surrounding the woman and snake were uncanny, predatory figures, looking like revellers in animal masks from a C20th folk-horror film. Words were inscribed on that picture: odd and meaningless enough to suggest magical incantations. I have no idea if the other pictures along the passageway were similar. My grandmother told me they were not, but I wasn’t taking any chances.

When I started to hear about supernatural events at Heol Fanog in the 1990s, that was the image I thought of. The figures in it, the odd words on it, both suggested rituals, spells, invocations, but I wanted to suppress that thought. I told myself that in the context of 1968, with its prog rock album covers, the picture was not all that strange, was it? But still my mind kept coming back to the image of a snake-wrapped woman and what it meant. And who created it? Was it someone interested in magical rituals who might, later on, have conjured a malign spirit by mistake?

The first clue came from my brother who remembered Mrs Holbourn being described as the ‘Laird of Foula’. That phrase had made little sense to me at the time. I was of an age where I felt I should ‘know’ things and was reluctant to ask adults if something puzzled me, even though my parents were willing explainers. I imagined Mrs Holbourn’s regal arrival on Foula that summer as a mixture of pagan warrior and the Queen dressed for Balmoral. After a little digging on the internet, I discovered that Marion Holbourn’s husband, Ian, had visited Foula around 1900, fell in love with the remote island and purchased it — as one does — proclaiming himself Laird of the island.

Ian Holbourn, aka John Bernard Stoughton Holbourn, was a fascinating character. He originally trained as an artist and architect; was a poet and writer; lectured in art and archaeology; co-founded Ruskin College, set up to provide educational opportunities for working class men who would not otherwise have been able to study at Oxford. He married Marion Archer-Shepherd in 1904, survived the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, and died in 1935.

Foula was no Wicker Man ‘Summer Isle’ — more presbyterian than pagan, I would say. Legend gives it the ancient name of Ultima Thule. As I read more about the place, I came across an interesting nineteenth century character: the writer, illustrator and political cartoonist, John Sands, who had spent time on Foula and other remote Scottish Islands before Ian Holbourn arrived. He fought against what was then a common local economic practice called the Truck System, whereby wages were paid not in real money, but as payment ‘in kind’; given as credit with local suppliers, or as tokens and vouchers.

The V&A keeps a small John Sands archive, mostly sketches from local life rather than satirical drawings. My shock of recognition came later though, on Wikipedia, reading a description of one of his political cartoons where Sands:

“drew Foula as a beautiful young woman being strangled by a boa-constrictor labelled ‘landlordism’ watched by other reptiles called ‘missionary’; ‘laird’ and ‘truck’ ”. (Wikipedia credits this description as: Nicolson, J, 3 July 1937, John Sands, Shetland Times.)

“Landlordism”? “Missionary”? “Laird”? “Truck”? I am sure these were the four odd words on the Heol Fanog picture. The description of the chimeric creatures and the snake-wrapped woman fits too. Not a satanic, supernatural image after all, not an abracadabra spell, but a political cartoon. It makes sense, I think, that the Holbourn family ended up with that illustration.

~~~~~~~

This has been an unexpected journey but it wasn’t one taken with any particular intent. I certainly didn’t set out to prove that Heol Fanog was haunted or that it wasn’t, or to disprove the later experiences of the Riches there in the 1990s. After all, didn’t they experience one blissful summer up there too, like mine, before the terrifying apparitions arrived?

I’ve been past Heol Fanog a number of times in more recent years, travelling with my husband and friends; it is the loveliest route for a walk up the mountain. Each time we passed it, the house was harder to find: lower, further back from the road than I remembered, the trees around it denser and taller. I think it was on the last journey that I saw the sign — the Danger sign, often seen as a child, warning of manoeuvres at the military firing range. Except that… I couldn’t have seen it. The firing range ceased activity well before then, had wound up by late 80s when the Rich family arrived, though the army maintained a base for non-flash-and-bang type manoeuvres for a while, I believe.

At the end of my story, a small mystery remains, because, if we didn’t see the firing range sign on that trip, and my memory tells me we did, why did we take the long way round? That was the day, surely, when we got lost and ended up in the wake of a tractor strimming high hedgerows along the narrow lanes.

The dense wall of newly cut green, the summer trees meeting overhead, the clippings of bracken and wildflower leaf covering the road — we were in a tunnel, glowing as green as an entrance to the world of the Tylwyth Teg. Our plight was just down to my poor map-reading skills, or so those with more sense would say.

In a narrow mountain lane, blocked by mechanical activity up ahead and a long, steep track behind you, with no turning places or chance of safe reversal, you can’t go back and the best you can do is wait patiently. Memory is the strangest part of my story in the end.

© Sarah Williams December 2022

Leave a reply to Louiseasy Cancel reply