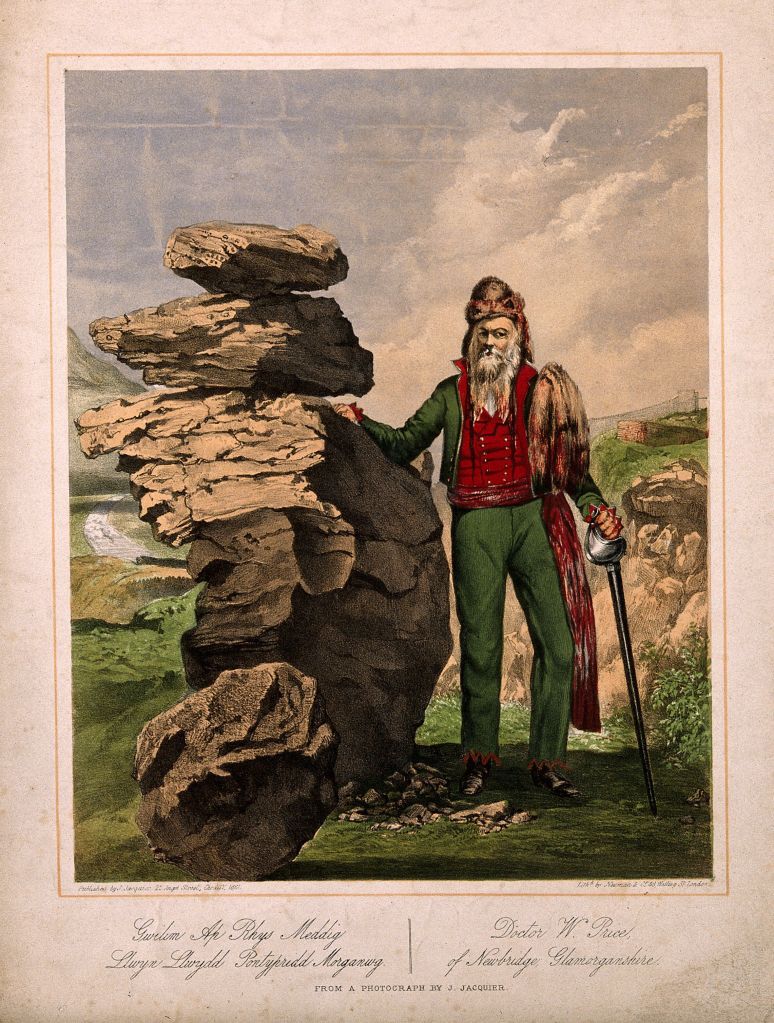

A few years ago, I was fortunate enough to be part of a team that wrote and led tours at Wellcome Collection in London. One particular tour started with this painting: William Price of Llantrisant. Tours are driven by the audience, and the picture always took us off on quite a journey: C19th medical training; the origins of the NHS; political protest; how we treat the dead, and even ‘awen’ or poetic inspiration. What follows is a very short summary of William Price’s long and full life. For those who want to know more, I recommend the wonderful books by the late Dean Powell of Llantrisant.

William Price looks down on all but the tallest visitor in the gallery, his austere expression at odds with his flamboyant outfit. His name, William Price of Llantrisant, sometimes surprises the audience when they discover he only moved to Llantrisant when he was in his seventies. A string of accolades and accusations usually follow his name: physician, eccentric, radical, activist, druid, inventor of the onesie, pioneer of cremation.

We don’t know quite so much about the two dappled goats at his feet.

The setting for the painting is South Wales, in the uplands familiar to me from childhood: sheep-cropped, tussocky grass; gorse, rock rose and foxglove; sunlight on a bald, brown hill; the ruins of a castle tower. Price’s druidic regalia comes complete with fox fur hoodie, and, if we could peer closely enough, we might see goats again – cast on his fine bronze buttons. The label dates the painting to 1918, twenty-five years after William Price died. The figure of the doctor is a little wooden, perhaps because it has been copied from a lithograph created c.1870 while Price was still alive. There is a picture in Pontypridd museum, by an unknown artist, showing Price in a similar pose.

Why is this painting here in Wellcome Collection? The museum’s founder, Henry Wellcome, was on an endless quest to represent human history, and if Henry couldn’t acquire a significant moment in the form of an object, he would sometimes acquire a picture of it instead. Welsh artist A C Hemming was most likely commissioned by Henry Wellcome to depict this scene.

As to the scene itself: in a moment William Price is going to move left out of the painting with flaming torch, along the hillside in the gathering dusk. He is waiting for the moment, that cold winter evening in 1884, when the population of Llantrisant spills out of chapel to witness him in full regalia, setting light to a pyre.

That event – of which more soon – had far-reaching consequences, and has overshadowed everything in Dr Price’s life. There are other stories to be told before we get to it, however.

Medical training

Scarificator with six lancets used for blood-letting, 19th century. Wellcome Collection

William’s medical ambitions may have been inspired by what happened to his father. The elder William Price went up to Oxford a sane man but came back to Rhydri (Rudry) a changed man, unable to fulfil his ambition of going into the church. Eccentric behaviour – wandering naked in the hills, bathing fully dressed in local ponds, pocketing adders – shaded into what might be described as psychotic behaviour today, and this was accompanied by violent rages that his wife, Mary Edmunds, and their small children had to cope with. Mary had been a servant before marriage and their match had further alienated the family from the rest of the comfortable Price gentry; there was little help from them as William grew into an exceptionally bright young man with an interest in medicine.

Welsh was the language of the home and, in calmer moments, William’s father taught the boy Latin. William was ten when he went to school and learnt English then. He must have learnt fast… must have been a remarkable pupil because, aged thirteen, he is apprenticed to a local young and talented surgeon, Evan Edwards, the grandson of William Edwards who built Old Bridge at Pontypridd. After a five year apprenticeship, Price spent a year working in London hospitals. This included the London Hospital in Whitechapel where he would come across the same illnesses, the result of poverty, that he would encounter on his return to a rapidly industrialising South Wales. Dr William Price became one of the youngest ever Members of the London College of Surgeons in 1821.

Skilled surgical techniques, as practiced by his mentor Edwards, formed a significant part of nineteenth century medicine, but Joseph Lister’s developments in antiseptic surgery were some forty years away and contemporary accounts of operations carried out without anaesthesia chill us today. Medicine in general was still dominated by the Four Humours and treatments aimed to achieve their balance, such as purging or blood-letting.

The future looked promising for a highly skilled physician returning home, yet, sixteen years later, William is on the run with a price on his head, in exile in Paris.

The progressive Dr Price

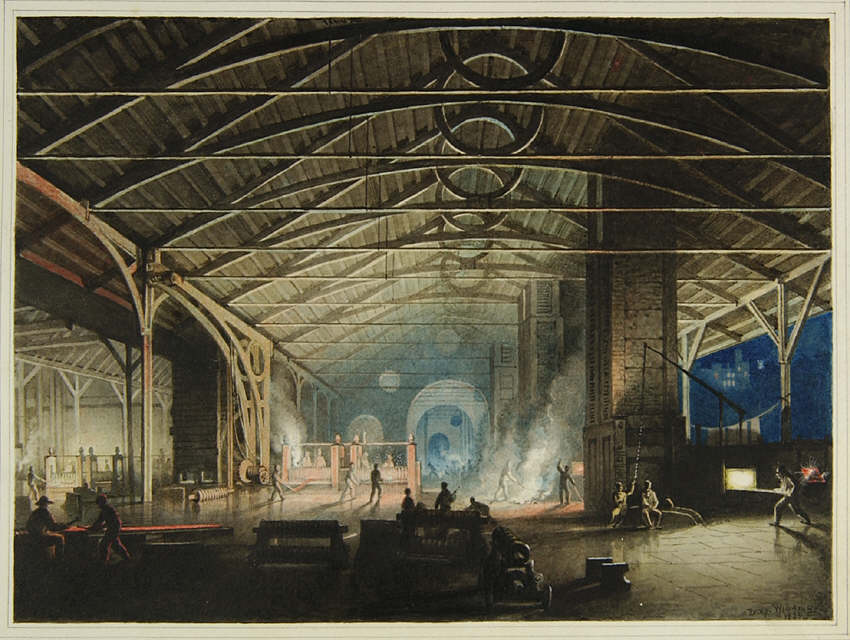

Cyfarthfa Ironworks Interior at Night, by Penry Williams, 1825, Casgliad y Werin Cymru

Price’s first surgery was in a hamlet near Pontypridd, then little more than a village itself, but growing fast – as was much of that part of South Wales. Industries there were largely owned by English ironmasters and the workers were subject to terrible living and working conditions.

Price was scathing of many of his fellow physicians, referring to them as “peddlers of poison”. Voltaire’s epigram “the art of medicine consists in amusing the patient while nature cures the disease” comes to mind at times. Price’s horror of smoking and meat-eating would have seemed as amusing to patients then as his theories about the ill effects of sock-wearing and the benefits of naked rambles.

He became physician to the Treforest Tinplate works and then to the Brown Lenox Chainworks. There he instituted a system whereby workers paid him a small regular fee while they were well and were treated ‘for free’ when sick: a prototype medical aid society. A later example, Tredegar Medical Aid Society, became famous when Aneurin Bevan, introducing his 1948 legislation that established the NHS, said, “All I am doing is extending to the entire population of Britain the benefits we had in Tredegar for a generation or more. We are going to ‘Tredegar-ise’ you.”

Price must have been a charming man, and one trusted by the workforce – but he hung out with the bosses too. His interest in neo-Druidism appealed to one of the local ironmaster’s sons, Francis Crawshay, and together the two men explored an interest in esoteric religion and mythology.

There was one formidable character William Price ultimately failed to charm, however, and that was the heiress and patron of the arts, Lady Llanover. It was on her land that the doctor attempted, over many years, to set up a ten-story museum of Welsh history and culture. All that remains of this grand plan are the pair of intriguing gate houses, known locally in Pontypridd as the Round Houses of Glyntaff.

William Price at Y Maen Chwyf. Lithograph, Newman & Co, 1861, Wellcome Collection

It seemed natural that Price, with his radical views and the trust of working men, would become a local Chartist leader, campaigning for the extension of the franchise. Price held meetings about the people’s charter at Y Maen Chwyf, a significant stone formation in Pontypridd: where Iolo Morganwg had organised a Gorsedd, a convention of Druidic bards, many solstices ago.

Price didn’t trust the local Chartist leaders enough to take part in the 1839 March on Newport, but, despite this, when the rebellion failed, he was implicated and fled the country, £100 on his head.

In exile in Paris, Price would have an epiphany.

Enter the Druids

The druids: or the conversion of the Britons to Christianity.

Engraving S.F. Ravenet, 1752, Wellcome Collection

Greek and Roman accounts of Druids are somewhat contradictory and vague, frequently portraying them as frightening and barbarous. So it is surprising that, from the late seventeenth century, they start to be portrayed as wise, cuddly, nature-loving figures.

Ronald Hutton has described how growing nationalist sentiments of the period across Europe, together with revived interest in the classics by humanist scholars, piqued interest in the mysterious Druids. Perhaps Wales, its language and sense of identity in peril, needed Druids?

Just as John Aubrey, out hunting one winter’s day in 1648, had ‘seen’ as if for the first time the massive stones surrounding the village of Avebury and came to ‘read’ them as sacred druidic sites, self-proclaimed bard Iolo Morganwg believed he could decode lost knowledge about the Druids from medieval Welsh verse. Unfortunately, some forgery and quite a lot of laudanum were involved in Iolo’s method.

We don’t know exactly what the exiled Price saw at the Louvre that led to his epiphany, but he described it as a stone containing an ancient Welsh script that only he could decipher; its message was, in part, that he would father a Druidic messiah.

Dean Powell speculates that the stone might have been part of a temporary exhibition and notes that Price set great store by a particular book and a particular engraving depicted in it (see above). This image is an Abraxas stone, a Gnostic amulet. Note its influence on the bardic ‘onesie’ William Price designed!

End times

Left: from Bernard de Montfaucon’s L’Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures, 1719.

Right: William Price in a costume inspired by it, on stage, 1884. National Museum of Wales

Price’s exile wasn’t long, and in the 1880s, we find a still vigorous Price living in Llantrisant with local woman Gwenllian Llewellyn, some sixty years his junior. His philosophy of free love – one that sought to free women from the enslavement of marriage – could be interpreted as a convenient one as far as Price was concerned.

When Gwenllian gave birth to a son, the prophecy – the insight and inspiration that had descended on Price all those years ago in Paris – seemed to have been fulfilled and they named their boy Iesu Grist (Jesus Christ). The story is a sad one: the boy was sickly from birth and died at only five months. And so we find Price high in his goat field one winter’s night in 1884, lighting a pyre – a means to the afterlife, perhaps, for a druidic messiah. The intervention of horrified villagers and the local constabulary prevented the child’s cremation and led to Price’s arrest.

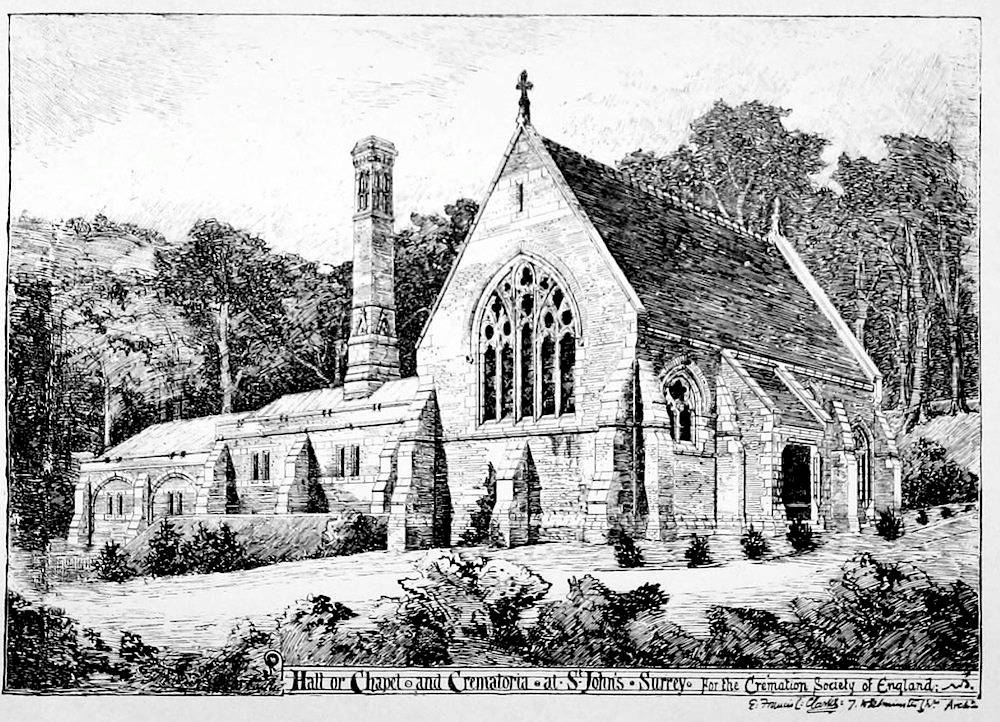

Price was fortunate to come before a judge sympathetic to the aims of the The Cremation Society of Great Britain. This was set up in 1874 to campaign for the legalisation of cremation, a practice the Church objected to on a number of grounds, not least because of how cremated bodies would fare at the Resurrection. Price would echo some of the Society’s arguments in his defence: “It is not right that a carcass should be allowed to rot and decompose in this way. It results in a wastage of good land, pollution of the earth, water and air, and is a constant danger to all living things.”

Chapel and crematoria at St Johns, Surrey, 1889, Wellcome Collection

Price was found not guilty and the verdict set a precedent. A unused crematorium, built in the 1870s by the Cremation Society at St John’s, Surrey, was able to open and several private cremations took place. This was followed by the passing of the Cremation Act of 1902.

Price himself was cremated in 1893. His carnival of cremation was planned in detail by Price before his death and carried out by Gwenllian; it is said that the pubs of Llantrisant ran dry that day.

What about the prophecy? In the years between Price’s acquittal and death, a second Iesu Grist had been born, and this boy thrived despite his name – though he is said to have been a strongman and wrestler for a while! (To be fair, that could have been more to do with his adventurous nature than his name, because Gwenllian re-named him Nicholas not long after her husband’s death.)

Gwenllian herself settled down to a quieter life in the area with a former roads inspector and publican, John de Winter Parry.

After the fire

In 1966, Price’s daughter, Penelopen, unveiled stained glass windows in Glyntaff crematorium chapel near Llantrisant. The image of Christ’s resurrection was conventional, but “…to one side…was a pane containing a peacock, a creature whose flesh was, according to ancient myth, incorruptible. On the other was a phoenix, the legendary bird that rose again from its own ashes. The windows were a bid to make sense in coloured glass of the Church’s teachings about death, teachings in need of a new metaphor now that cremation was, for many, the gateway to resurrection and eternal life.” From Carl Watkins’ The Undiscovered Country: journeys among the dead.

National Cremation Statistics show that in the 1960s, when Penelopen unveiled the chapel windows, 34% chose cremation over burial. By 2013 that figure was 75%.

This will not be the last time we need to find a new metaphor about the human journey after death. As of February 2023, the Church of England is considering supporting more environmentally-friendly methods of disposing of dead bodies such as aquamation and human composting.

I wonder, would Dr William Price approve?

Note: as of Spring 2023, the painting of Williams Price is no longer on view at Wellcome Collection – the gallery it hangs in is temporarily closed.

© Sarah Williams March 2023

Leave a comment